I keep seeing this shirt all over the internet although I have yet to see any hipsters in person actually wearing it. Its pretty funny check it out. There are a few other versions of it out there like a zombie one and even a weeping angel from Doctor Who!

Cool shirt. But the nit-picking nerd in me has two problems with this. First off is the model's hands. I have mentioned before theropods like Tyrannosaurus couldn't bend their wrists that way! So if anyone reading this buys this shirt you now have no excuse for improper wrist posture!

Second is their use of the term "T-rex". "T-rex" is wrong. The proper term is T. rex. The full term, Tyrannosaurus rex is actually the full two-part scientific name of the animal. Tyrannosaurus is the genus and rex is the species. Just like Canis familiaris is for a dog. All known organisms have a two part scientific name. Extinct animals rarely are given common names unlike most modern animals (dog, tiger, human...). It just makes it easier to say the scientific name since its the same word all over the world, regardless of what language you speak. For most dinosaurs, we just say their genus when talking casually. Triceratops, for instance is actually Triceratops horridus or Triceratops prorsus (there are two species) when said fully. For some reason Tyrannosaurus' species name is cool sounding (Go ahead say it out loud...rex. Yeah its totally cool.) so we tend to say it fully for fun. A lot of people have no clue what it really is that they are saying though.

So where did the term "T-rex" come from? Often times, especially when writing a scientific paper, it can become tiresome to write a full genus and species name over and over again. To deal with this, we can simply put the first letter of the genus (in this case T) with a period and then the species name for an abbreviated version. When applied this gives us T. rex. Oh and in case you were wondering, scientific names should always be in italics.

So why do we always see T-rex and not T.rex? Honestly I don't know. Apparently somewhere along the line somebody decided that dashes were cooler than periods and therefore messed up everyone's writing of the most famous dinosaur of all time. Yay for pop culture!

The shirt itself can be bought here. If you have this shirt (or any other dinosaur-theme apparel) take a photo of yourself wearing it and put it up on our facebook page!

Pages

▼

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

Thursday, November 1, 2012

Interview with Paleontologist: Dr. Adam Stuart Smith

Dr. Adam S. Smith is a palaeontologist and curator at the Nottingham Natural History Museum, UK. He specializes in plesiosaurs and other fossil marine reptiles from the Mesozoic Era and has co-named two new plesiosaurs: Meyerasaurus and Lusonectes. He runs several palaeontology websites: 'The Plesiosaur Directory' (http://www.plesiosauria.com), which all about plesiosaurs; and The Dinosaur Toy Blog (http://www.dinotoyblog.com), which is all about prehistoric animal models. I have had the pleasure of being friends with Dr. Smith for a few years now and was very excited when he agreed to be interviewed for Jersey Boys Hunt Dinosaurs!

Question 1:

You are one of my heroes in the field of paleontology. Who did you admire growing up?

AS: The vertebrate palaeontologist I was most aware of growing up was Professor Michael Benton. I read a lot of his books. So, when I went to the University of Bristol to study palaeobiology it was great to finally meet him, and even better that he was my supervisor during my Masters project on plesiosaurs.

Question 2:

At what age did you get inspired to pursue a career in paleontology?

AS: From a very early age, I always wanted to be a palaeontologist and always had my head in a dinosaur book.

Question 3:

What was your favorite dinosaur (or other prehistoric creature) growing up? What dinosaur is your favorite now?

AS: My favourite dinosaur growing up was the scaly old version of Deinonychus. Today - I don’t know - there are so many more to choose from! I have a favourite plesiosaur though: Attenborosaurus.

Question 4:

Paleontology is such a diverse field these days involving many disciplines. What advice would you give to an aspiring paleontologist today?

AS: On one hand, play to your strengths. Some people are better at maths, or drawing, or spotting fossils in the field, or something else. That’s what makes you stand out in the crowd, and it is probably what you enjoy most, so harness and develop those skills. On the other hand, it is vital to get as broad an education as possible. As happened with the dinosaurs, if you become too specialised you risk becoming extinct, so a balanced set of skills and knowledge is important.

Question 5:

Going to college these days and then on to grad school has become a daunting task. Many people are unaware of how long it takes to make it to the finish line. The rewards are great, but what would you say to someone pursuing professional studies after college?

AS: It completely depends on the person: what are their motivations, their aspirations, what do they want to achieve? Going to university doesn’t guarantee a job in this ever-competitive world, so depending on what field you want to go into, it may be necessary to do voluntary work to gain experience that university courses can’t provide. For example, I got my first work experience by volunteering in museums and helping at education events. This was a necessary first step for me to get on the employment ladder.

Question 6:

What was or is your favorite research project? What are some of your current projects?

AS: I don’t know if I have a favourite research project, I don’t think about my research in that way. I suppose I have fondest memories of my PhD research on rhomaleosaurid pliosaurs as I traveled around a lot to different museums collecting data. I have a few current research projects. For example, I’m working on a fantastic pliosaur specimen from Lyme Regis, which I think is a new species.

Question 7:

Jurassic Park and Land Before Time (opposite ends of the spectrum I know) were the movies I remember as a kid that fueled my passion for dinosaurs. What was your most memorable movie, book or TV program that inspired you with regards to peleontology?

AS: It was Jurassic Park as well. It was released when I was 13, perfect timing for a young teenager with a passion for dinosaurs. I’m sure I would have pursued a career in palaeontology anyway, but Jurassic Park surely put some fuel on the fire.

Question 8:

I remember meeting my first professional paleontologist. Do you remember the first paleontologist you ever met? Were you a nervous wreck?

AS: I think the first vertebrate palaeontologist I ever met was Dr David Martill who I met when I first went to university. Dave was an advisor for the BBC series Walking with Dinosaurs and I recall being rather impressed by that!

Question 9:

Dinosaurs and the animals that lived at the same time as them were amazing creatures. Why do you feel they continue to fascinate us?

AS: Prehistoric animals are so weird and wonderful and the world they lived in is so far away. But it all happened right here and that allows the imagination to run wild. Dinosaurs are the closest thing we have to real monsters. They are frightening, fantastic, mysterious, but most importantly, real. Why are people fascinated by towering animals that could swallow you whole? The answer is in the question!

Question 10:

What is your favorite time period?

The Jurassic. When plesiosaurs first came on the scene.

Question 11:

The time span in which the dinosaurs lived in was huge. How do paleontologists remember all that information from such a vast era? Do paleontologist focus on one particular subject?

AS: Palaeontologists do tend to specialize on particular groups of organisms or specific fields of research, but it is important to have an understanding of the bigger picture to put the various topics into a greater context. As for remembering all that information, we don’t always. I’m constantly forgetting things. That’s why we have notebooks and why it’s important for palaeontologists to publish our findings - I frequently consult my own articles!

Thank you Dr. Smith! For anyone who is interested here and here are his websites again. Join me next week for another post!

Question 1:

You are one of my heroes in the field of paleontology. Who did you admire growing up?

AS: The vertebrate palaeontologist I was most aware of growing up was Professor Michael Benton. I read a lot of his books. So, when I went to the University of Bristol to study palaeobiology it was great to finally meet him, and even better that he was my supervisor during my Masters project on plesiosaurs.

Question 2:

At what age did you get inspired to pursue a career in paleontology?

AS: From a very early age, I always wanted to be a palaeontologist and always had my head in a dinosaur book.

Question 3:

What was your favorite dinosaur (or other prehistoric creature) growing up? What dinosaur is your favorite now?

AS: My favourite dinosaur growing up was the scaly old version of Deinonychus. Today - I don’t know - there are so many more to choose from! I have a favourite plesiosaur though: Attenborosaurus.

|

| Dr. Smith working on making a cast model of Attenborosaurus, a plesiosaur named in honor of naturalist, David Attenborough. |

Question 4:

Paleontology is such a diverse field these days involving many disciplines. What advice would you give to an aspiring paleontologist today?

AS: On one hand, play to your strengths. Some people are better at maths, or drawing, or spotting fossils in the field, or something else. That’s what makes you stand out in the crowd, and it is probably what you enjoy most, so harness and develop those skills. On the other hand, it is vital to get as broad an education as possible. As happened with the dinosaurs, if you become too specialised you risk becoming extinct, so a balanced set of skills and knowledge is important.

Question 5:

Going to college these days and then on to grad school has become a daunting task. Many people are unaware of how long it takes to make it to the finish line. The rewards are great, but what would you say to someone pursuing professional studies after college?

AS: It completely depends on the person: what are their motivations, their aspirations, what do they want to achieve? Going to university doesn’t guarantee a job in this ever-competitive world, so depending on what field you want to go into, it may be necessary to do voluntary work to gain experience that university courses can’t provide. For example, I got my first work experience by volunteering in museums and helping at education events. This was a necessary first step for me to get on the employment ladder.

Question 6:

What was or is your favorite research project? What are some of your current projects?

AS: I don’t know if I have a favourite research project, I don’t think about my research in that way. I suppose I have fondest memories of my PhD research on rhomaleosaurid pliosaurs as I traveled around a lot to different museums collecting data. I have a few current research projects. For example, I’m working on a fantastic pliosaur specimen from Lyme Regis, which I think is a new species.

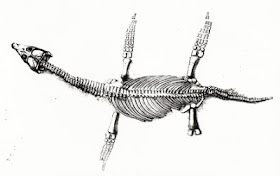

|

| Illustration of a Rhomaleosaurid skeleton. |

Question 7:

Jurassic Park and Land Before Time (opposite ends of the spectrum I know) were the movies I remember as a kid that fueled my passion for dinosaurs. What was your most memorable movie, book or TV program that inspired you with regards to peleontology?

AS: It was Jurassic Park as well. It was released when I was 13, perfect timing for a young teenager with a passion for dinosaurs. I’m sure I would have pursued a career in palaeontology anyway, but Jurassic Park surely put some fuel on the fire.

Question 8:

I remember meeting my first professional paleontologist. Do you remember the first paleontologist you ever met? Were you a nervous wreck?

AS: I think the first vertebrate palaeontologist I ever met was Dr David Martill who I met when I first went to university. Dave was an advisor for the BBC series Walking with Dinosaurs and I recall being rather impressed by that!

Question 9:

Dinosaurs and the animals that lived at the same time as them were amazing creatures. Why do you feel they continue to fascinate us?

AS: Prehistoric animals are so weird and wonderful and the world they lived in is so far away. But it all happened right here and that allows the imagination to run wild. Dinosaurs are the closest thing we have to real monsters. They are frightening, fantastic, mysterious, but most importantly, real. Why are people fascinated by towering animals that could swallow you whole? The answer is in the question!

Question 10:

What is your favorite time period?

The Jurassic. When plesiosaurs first came on the scene.

|

| Plesiosaur, Elasmosaurus illustration by Dr. Adam Stuart Smith. |

Question 11:

The time span in which the dinosaurs lived in was huge. How do paleontologists remember all that information from such a vast era? Do paleontologist focus on one particular subject?

AS: Palaeontologists do tend to specialize on particular groups of organisms or specific fields of research, but it is important to have an understanding of the bigger picture to put the various topics into a greater context. As for remembering all that information, we don’t always. I’m constantly forgetting things. That’s why we have notebooks and why it’s important for palaeontologists to publish our findings - I frequently consult my own articles!

Thank you Dr. Smith! For anyone who is interested here and here are his websites again. Join me next week for another post!

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Dinosaur Feathers: First North American Find

Its no secret that certain dinosaurs had feathers at this point. This is largely due to the abundant fossils from places like China and a few from Europe that clearly show evidence of plumage on beautifully preserved theropod skeletons. In 2008, however, the first ever dinosaurs from North America were discovered with actual feathers.

The dinosaur is not a newly discovered species, its called Ornithomimus and was a very close relative to Struthiomimus which has been talked about previously on this site. Two adults and one juvenile were found, all three possessing evidence of plumage. The younger animal has what appears to be fluffy down-type feathers like modern juvenile birds and the adults had quill knobs, like those found on Velociraptor skeletons, proving that it would have had large, wing-type feathers on its arms. Whats interesting is that veined, wing feathers are usually implications of flight, looking at modern birds. Ornithomimus clearly wasn't much of a flyer, however. It would have been too large and heavy. This discovery suggests that perhaps these feathers were originally evolved for something like sexual display or brooding (also observable in modern birds) and later were adapted for flight in certain kinds of animals (not Ornithomimids).

It has been assumed for a while now that Ornithomimids (family of dinosaurs Ornithomimus belongs to) had feathers. Its only logical to think this way since every other type of dinosaur surrounding them on the theropod family tree (Tyrannosauroids, Oviraptorids, Dromaeosaurids, Therizinosaurids, Compsognathids, birds...) has at least one specimen on the fossil record that clearly shows feathers in some form or another. Ornithomimids were the only ones that didn't...until now. The icing on the cake is that its in North America too! On that note I also should mention this discovery also kills any misconceptions that some people may have had thinking only feathered dinosaurs came from places like China. In reality feathered dinosaurs were all over the world, many of them already discovered in the form of skeletons and bones where the feathers didn't preserve like Deinonychus, for instance. Fossilization is rare to begin with let alone preservation of soft tissue!

Works Cited

Hartman, Scott. "Skeletal Drawing: Ornithomimus Had Wings...as an Adult." Skeletal Drawing: Ornithomimus Had Wings...as an Adult. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012. <http://skeletaldrawing.blogspot.ca/2012/10/ornithomimus-had-wingsas-adult.html>.

"Dinosaurs May Have Evolved Feathers for Courtship." NewScientist- Life. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012. <http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn22428-dinosaurs-may-have-evolved-feathers-for-courtship.html>.

|

| Fossil feathers from one of the Ornithomimus specimens at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Canada |

It has been assumed for a while now that Ornithomimids (family of dinosaurs Ornithomimus belongs to) had feathers. Its only logical to think this way since every other type of dinosaur surrounding them on the theropod family tree (Tyrannosauroids, Oviraptorids, Dromaeosaurids, Therizinosaurids, Compsognathids, birds...) has at least one specimen on the fossil record that clearly shows feathers in some form or another. Ornithomimids were the only ones that didn't...until now. The icing on the cake is that its in North America too! On that note I also should mention this discovery also kills any misconceptions that some people may have had thinking only feathered dinosaurs came from places like China. In reality feathered dinosaurs were all over the world, many of them already discovered in the form of skeletons and bones where the feathers didn't preserve like Deinonychus, for instance. Fossilization is rare to begin with let alone preservation of soft tissue!

.jpg) |

| Struthiomimus I painted earlier this year with incorrect featherless arms. |

|

| Luckily I was able to correct it! |

Works Cited

Hartman, Scott. "Skeletal Drawing: Ornithomimus Had Wings...as an Adult." Skeletal Drawing: Ornithomimus Had Wings...as an Adult. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012. <http://skeletaldrawing.blogspot.ca/2012/10/ornithomimus-had-wingsas-adult.html>.

"Dinosaurs May Have Evolved Feathers for Courtship." NewScientist- Life. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012. <http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn22428-dinosaurs-may-have-evolved-feathers-for-courtship.html>.

Saturday, October 13, 2012

Shoprite Toy Section: The Good Stuff

So I was grocery shopping the other day and happened to pass the toy section. The toy sections in grocery stores are small but usually contain a variety of different things. A common theme for toys is, no surprise, dinosaurs. Most little kids had a dinosaur phase (some of us don't grow out of it). A puzzle designed for toddlers happened to catch my eye that day because it was of dinosaurs (shocker). It had four typical cartoon-style dinosaurs, with bright colors and each dinosaur was labelled. To my surprise they were actually correctly labelled!

The Apatosaurus was called an Apatosaurus, not Brontosaurus! The theropod I was almost sure would be labelled as Tyrannosaurus or worse, T-rex(gasp!) despite the three fingers but alas, it was labelled Allosaurus! Even the pterosaur, which is is 99.9% of the time mislabeled as Pterodactyl (an actual genus of animal but not usually what people picture) on toys like this was actually referred to as a pterosaur! The cartoon creature they have on the puzzle looks like its supposed to be Pteranodon, a kind of pterosaur, so they are safe. Good job, grocery store discount toddler puzzle! You have the Jersey Boy Hunts Dinosaurs stamp of approval!

The Apatosaurus was called an Apatosaurus, not Brontosaurus! The theropod I was almost sure would be labelled as Tyrannosaurus or worse, T-rex(gasp!) despite the three fingers but alas, it was labelled Allosaurus! Even the pterosaur, which is is 99.9% of the time mislabeled as Pterodactyl (an actual genus of animal but not usually what people picture) on toys like this was actually referred to as a pterosaur! The cartoon creature they have on the puzzle looks like its supposed to be Pteranodon, a kind of pterosaur, so they are safe. Good job, grocery store discount toddler puzzle! You have the Jersey Boy Hunts Dinosaurs stamp of approval!

Friday, October 5, 2012

Breast Cancer Awareness Month: Pachy goes Pink

Earlier this week fellow Jersey Boy, Gary, called me up to share with me an idea he had for the blog. He suggested I paint a pink dinosaur in honor of breast cancer awareness month (October...now). I have seen other paleo-artists do this in the past and always liked their work so I was immediately on board with the idea. Here she is, the pink, breast cancer awareness Pachycephalosaurus!

If you would like to donate to help fund breast cancer research (not just awareness, actual research for a cure.) you can do so right here.

If you would like to donate to help fund breast cancer research (not just awareness, actual research for a cure.) you can do so right here.

Thursday, September 27, 2012

Jersey Boy Visits Maryland

Two weeks ago my cousin was married (congratulations again if you are reading this!) in Maryland. When I got the news that I would be making a trip down for a weekend the first thing my dinosaur-obsessed brain thought was "Hey, Dr. Thomas Holtz is a professor there!". Dr. Holtz is a well known paleontologist who does most of his work studying tyrannosaurids. He was also featured in this blog's very first post earlier this year. I promptly contacted him and asked if he would be teaching that Friday and to my delight he told me he was and I was more than welcome to sit in on his lecture. I ended up having wake up at 5 AM to drive four and a half hours from New Jersey down to the University of Maryland for his 10 AM lecture. It was totally worth it though. Lets just say I wish all college professors were as excited about their subject as he is. After lecture was over we went to his office and talked dinosaurs for a few hours.

|

| Dr. Thomas Holtz and I at the University of Maryland |

Keep in mind I drove down myself. The rest of my family wasn't getting down there until later that evening and I couldn't check into the hotel room until later that afternoon! What to do, what to do....oh yeah, duh. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History is just a short drive away! Now, living in NJ, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City is just a few minutes away for my house. That being said, I am spoiled when it comes to dinosaur museums but I must say the National Museum did not disappoint!

|

| National Museum's Dinosaur Hall. |

They had a lot of cool skeletal mounts. My favorite thing there probably had to be their Triceratops (My favorite dinosaur...I'm biased). They had a skeleton, a skull in a glass box, a cast of a horn you could touch and a newer video playing showing how scientists currently think the animal would have moved. You can actually see this video and some other neat pictures on their website here if you can't make the trip down to see it in person yourself.

| ||

| Triceratops at the National Museum |

|

| Just think. Somebody had to make that. |

One unique fossil there on display that I took a liking to was called a Deomonelix or "Devil's Corkscrew". I actually learned about it in Dr. Holtz's lecture earlier that day. Its a trace fossil in the form of a burrow dug out by a prehistoric beaver (existed after the dinosaurs but before us). The burrow filled in and created a mold complete with the poor animals remains at the bottom. What a neat find!

|

| Deomonelix on display at the National Museum. See the beaver skeleton at the bottom? |

All in all it was a successful trip. I didn't even mind the fact that my car was towed while I was in the museum. (Stupid DC parking laws. How was I supposed to know I was blocking rush hour traffic!?!?)

|

| My sister and I at the wedding reception the day after. Yes, there are dinosaurs on my tie. |

Join me next week for another sexy, dinosaur-related post! Also if anyone is interested Dr. Thomas Holtz has a twitter account right here. Also you can purchase some of his books here and here. See you next week!

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Interview with Paleoartist: Larry Felder

Fellow artist and friend of mine, Larry Felder, is probably most well known for illustrating and co-writing the popular dinosaur book, In the Presence of Dinosaurs. As an artist, Larry combines his skill and sensitivity as a wildlife artist with the keen eye and vivid perspective of a dedicated wildlife photographer to create images of long extinct creatures that appear almost real. It is because of this distinct life in his paintings that cause Larry's art to stand out amongst the best of them.

In addition to being a fantastic painter, Larry is also a very nice guy. He and his family attended my lecture, "The Real Dinosaurs", twice! Today I am going to share with you his interview for Jersey Boys Hunt Dinosaurs!

Question 1: How long have you been interested in paleontology? Who did you admire

growing up?

In addition to being a fantastic painter, Larry is also a very nice guy. He and his family attended my lecture, "The Real Dinosaurs", twice! Today I am going to share with you his interview for Jersey Boys Hunt Dinosaurs!

|

| Larry Felder |

|

| Larry's book, In the Presence of Dinosaurs |

Question 1: How long have you been interested in paleontology? Who did you admire

growing up?

LF: I've been interested in Paleontology pretty much since I first became aware of the subject as a kid. I kind of subscribe to the adage that all kids are into dinosaurs, it's just the lucky or sane ones that never outgrow it. And since I'll be 54 in September (ouch), that either makes me an old kid or a young middle-ager. So, I've been into paleo for about 50 years.

I remember reading about Roy Chapman Andrews and his forays to the Gobi, and since I was a visual person from the start (I've been drawing just as long), I was interested in the works of Charles Knight and Zdenek Burian. I've since become very good friends with Charles Knight's granddaughter Rhoda Kalt, which has a nice sense of symmetry.

|

| Tylosaurus by Larry Felder |

Question 2: At what age did you get inspired to pursue a career in paleontology?

LF: For me, it wasn't so much a decision to actively pursue a career in paleo. I've been painting and drawing since I could first hold a pencil and a paintbrush. It is so second-nature to me, like breathing, that it's not something I "pursued" so much as fell back into, when I realized there wasn't anything else that gave me the same kind of fire-in-the-belly feeling. And since I was into fossils and dinosaurs just as much as I was painting, it was a very small next step to put the two together and try and make something of it. It's been going on 25 years since I decided to do that.

Question 3:

What was your favorite dinosaur growing up? What dinosaur is your favorite now?

What was your favorite dinosaur growing up? What dinosaur is your favorite now?

LF: I'm not sure I ever had a 'favorite' dinosaur; it's more that I have a thing for a few groups. But if I had to pick one, it's Parasaurolophus. I like the hadrosaurs as a group, and the hypsilophodonts as well. I also like the smaller theropods. Part of my interest in them is my fascination with the life of Mesozoic Antarctica and Australia. The cool, temperate climate that had pronounced periods of daylight and dark is something unknown in contemporary ecosystems, and the adaptations of dinosaurs to those conditions is something I think is amazing. Hypsilophodonts and smaller theropods made up a decent part of those ecosystems, and it would have been just a blast to have watched them.

|

| Parasaurolophus nesting by Larry Felder |

LF: (This is a tough one!). It's like asking what is your formula for success. Paleontology is a unique discipline. I don't know of any other field that is as popular with the public that has so little actual funding in it. It is one of the stark realities of the field, so you can't go into it unless the fire is in your belly. But if it's there, I think you have to also have a sense of yourself, in so far as being able to draw attention to yourself in a positive manner, as well as having at least somewhat of a sense of business. This is also true for paleoartists as well (and artists in general). Maybe in the years to come, financing will become less of a pressing issue in the field, but it is an acute reality today, and you have to be able to think outside the box and consider the practical, financial realities of the field. I kind of liken it to major league baseball at the turn of the 20th Century, or Hollywood studios in the 30s and 40s. With both of these, the people who actually did the work were the ones who were compensated the least for it, because of the power structures of the time.

Today, paleontologists must compete for pennies on the dollar, while those on the peripheries of the field make more than those in it. For instance, Steven Spielberg and MIchael Chrichton probably made more on Jurassic Park than the entire field of paleontology has generated internally since the Great Dinosaur Bone Rush of the 1880s and 1890s. I'm not passing judgment on this; it's just the current reality, and anyone coming into the field needs a sense of being able to go outside the box and attract funding if they are going to be a success.

Question 5: Going to college these days and then on to grad school has become a daunting task. Many people are unaware of how long it takes to make it to the finish line. The rewards are great, but what would you say to someone pursuing professional studies after college?

LF: On this issue, there's a lot that paleontology has in common with other disciplines. We live in a push button/instant gratification society, where information is conveyed in sound bites, and if you can't explain it in 14 seconds or less, not only is it not important, it's not important to me whether I find out if it's important. Which means that in a way, we're getting what we expect, and unfortunately, deserve. All you have to do is watch JayWalking on the Tonight Show to find out. Show a person a picture of the Vice President or their own Senator and their jaws drop in confusion, but show them a picture of Justin Bieber, and they're off to the races. So it is with any field that requires more than the channel surfing level of commitment we've come to expect and demand out of education and life.

Bottom line, we need to reinforce to young people today that some things take time, and that just because you put grape juice in a bottle, don't expect it to become wine in a week. If Jersey Shore is going to be your intellectual high ground, like it's said, get used to asking "Would you like fries with that order?" as a career query, because that's all you're going to wind up with. Paleontology is near the top of the list of endeavors that require time, because when you think of it, we're studying things that are hundreds of millions of years old.

Many years ago, when Princeton used to have a Paleontology Department, I used to bring fossil footprints down to Dr. Donald Baird for him to identify (there was a lab assistant working there also at the time, a guy no one ever heard of, John Horner). On the door to the paleontology lab was a cartoon, a picture of a paleontology lab, with bones around. A paleontologist was standing there rubbing his chin, muttering to himself, "Now where did I put that bone? I only had it at my fingertips twelve years ago." Nothing describes paleontology better - it takes time to study things that are immersed in time, and you need to accept that reality from the start. If you don't, there are a lot of other things you could do. But if you understand that, it offers rewards that few other fields can match. So, I'd drill into young people today that you've been sold a false set of goods. They've been told or have been conditioned to expect things quick. I think this is an artifact of the advance in technology that we enjoy; people, especially young people, think that if we can push a button and get on line in an instant, my career shouldn't take so long. They're wrong, but there's a lot of them that think that way, and if they as individuals and we as a society are to grow, that thinking has to be acknowledged and challenged. There is a level of satisfaction that comes from working hard and long for some things that cannot be described, only experienced, and on top of that list is the study of ancient life. Also, paleontology is among the most democratic of fields. If you have good ideas and are not afraid to work hard, the field will embrace you, no matter who you are or where you come from. Bottom line; good things sometimes take time, and also, good things come to those who wait.

|

| Hesperornis by Larry Felder |

Question 6: What was or is your favorite project? What are some of your current projects?

LF: My favorite project up until now was my 2000 book, "In the Presence of Dinosaurs." I co-wrote it with my high school bio teacher, John Colagrande, and did all the illustrations. It was kind of a labor of love; we grew up with dinosaur books and both had our own collection, but wanted to do a book that we wanted to see, something that hadn't been done before, a general audience, dinosaur wildlife book. The chapters are based on ecosystems, not time periods, and the text is animal behavior, environmental and ecological considerations. The illustrations are dinosaur versions of contemporary wildlife photography. I had a great time writing and painting for it, and it was the only Time/Life book ever awarded a Starred Review in "Publisher's Weekly."

One aside; because it was a first of its kind, at the time, we encountered a lot of resistance from publishers, who as it turns out, are incredibly risk-averse. So it was an effort to bring it to fruition. One place that saw the book proposal and was very interested was the Discovery Channel. They had it in 1995. Four years later, they came out with Walking With Dinosaurs. If you look at the structure of the program and the book based on it, it is pretty much a carbon copy of our volume, down to the same animals, caption and chapter titles, and even the cover. They tweaked it just enough to cover their rears in copyright court. Even to this day, I'm asked "Why does your book remind me of Walking With Dinosaurs?" Well, turns out there was a good reason . . .

Right now, I'm working on a traveling exhibit of my work for museums and science centers, entitled, "Bringing Dinosaurs to Life." It's a combination of paintings, sculptures, fossil displays, and the source materials that paleoartists use to go from the bones in the ground to a believable restoration of what the animals may have looked like, and the world in which they lived. The question I get asked more than any other, when people see my work, is "How do you know what they really looked like?" The exhibit is based entirely around that one question.

I haven't done much painting in the past several years; I'm also finishing up a novel, a science thriller (not sci-fi, but fiction with a strong basis in science). I have maybe another month or two on it, then back to the easel.

Question 7: Jurassic Park and Land Before Time (opposite ends of the spectrum I know) were the movies I remember as a kid that fueled my passion for dinosaurs. What was your most memorable movie?

LF: I grew up when the sci-fi flicks of the 50s and 60s were just making their rounds on TV as repeat viewings. So I remember things like "The Giant Behemoth," "Beast from 20,000 Fathoms," and "The Valley of Gwangi." The special effects were, compared to today, well, dinosaurs, but they made an impression on you at the time that you just couldn't shake, the same way "King Kong" did for those who grew up in the 30s and 40s. Viewed today, they have a charming naivety that still holds up.

|

| Tyrannosaurus by Larry Felder |

Question 8: Do you remember the first paleontologist you ever met? Were you a nervous wreck?

LF: The first paleontologist I ever met actually was Dr. Baird. I really wasn't nervous that he was a paleontologist, but more nervous because I was in my late teens. So it was more of a teen-age apprehension. But since then, I've met many, and you have a kind of dual reaction; you're genuinely impressed and respectful of their accomplishments and stature, and also mindful of the fact that they're still human beings. Some are great guys; some are real characters! But they all are doing work that adds to our understanding of our world, and you know they will leave this LIfe a little better for their stay in it. And when you think of some of the vile things that some of us who call ourselves human beings do these days, you also realize that the world would be a hell of a lot better if there were more people like them in positions of authority.

Question 9: Dinosaurs and the animals that lived at the same time as them were amazing creatures. Why do you feel dinosaurs continue to fascinate us?

LF: Dinosaurs continue to fascinate us for several reasons. First, there is a mystery to them - no matter how much we learn about them, we're still separated from them in time, and there will always be things about them that we'll never know. And, they were living animals, and Life has an irresistable pull. It's why people still watch Animal Planet, and still go to zoos, and even throw bread crumbs in their backyard and watch birds (dinosaurs) feed. We are drawn to Life. And when the animals we think about with a sense of mystery turn out to have been ten and twenty times bigger than anything living today, the issue of scale asserts itself. It's said that dinosaurs are Nature's Special Effects, and they were. If no one knew they existed and we had to envision animals that would push the envelope of challenging our imaginations, it wouldn't be much of a stretch to come up with what Nature had already whipped up in the Mesozoic. They were beyond interesting and awesome.

There is one more aspect of this . Dinosaurs were for the most part incredibly elegant animals. Most mammals today are suped up versions of small, brown, round critters that scurried around in the night, and weren't much to look at. Think of a mouse or a rat, then think of a hippo or an elephant, or a wart hog. And think of the mammals that lived throughout the Cenozoic before man showed up. Many were, to say the least, not that attractive. They were complact, squat, with ugly bosses, bones and faces, with little or no tails, and very wide (a result of a reproductive system that passes large, fully formed young live, as opposed to laying small, narrow eggs).

Dinosaurs, even on a skeletal level, were much more elegant, with long tails, narrow hips (I'm excluding the nodosaurs and ankylosaurs here), and a riot of crests, horns, sails, etc., that spoke of an aesthetic standard that mammals rarely equal. Trust me; I'm a huge fan of the big cats, and a horse is among the most beautiful animals alive today. But if you compare the skeletal structure of a horse to any one of a number of dinosaurs, at the very least, they're equal, and as far as the dinosaurs, speak of animals that no doubt were the equal of today's most majestic mammals insofar as their level of attractiveness, and probably exceeded it.

Question 10: What is your favorite time period?

|

| Pteranodon by Larry Felder |

Question 10: What is your favorite time period?

LF: I have two, the Late Triassic/Early Jurassic boundary, because the area where I live contains rocks from that era, and it was a time when the dinosaurs were first getting their act together, and the Late Cretaceous (let's say, Judith River times). The dinosaurs then had evolved into incredibly diverse and elegant animals, occupying every ecological niche available. It would have been something to see what they would have evolved into had some of them made it past the K/T boundary. As for the Triassic/Jurassic time, I grew up collecting footprints from that era. The interesting thing about footprints is that they are the fossils of living animals. So you get running, standing, walking, tripping, slipping (animals in a rainstorm, for instance). They can be so fresh looking that they look like they were made six hours earlier. Bones are more spectacular, but in a subtle way, footprints are more intriguing.

That's it for this week, everybody! If you are interested in purchasing Larry's book (I highly recommend it if you are at all interested dinosaurs) you can purchase it right here. Join me next week as I share with you a recap of my journey down to Maryland!

Thursday, September 13, 2012

Painting Dryptosaurus: A Tutorial

This week I decided to follow up on my very first post and do another, more in-depth tutorial on paleo-art. This time we are going to go over the basics of watercolor painting! The animal we shall be painting is Dryptosaurus, in honor of Tyler Keillor's project.

Like all of my drawings, I must first start out with a rough sketch to make sure I am getting the proportions right. Unfortunately, Dryptosaurus is known from only several bones and not a full skeleton. When this happens my best bet is to reference close relatives to Dryptosaurus. Dryptosaurus was a tyrannosauroid but not a tyrannosaurid (confusing I know) so it was a bit more primitive than its big-headed, two-fingered cousins like Tyrannosaurus. When dealing with Dryptosaurus I look at animals like Eotyrannus and Appalachiosaurus as guides. Both of these dinosaurs are not only related to Dryptosaurus, but according to the bones on the fossil record, they visually resembled Dryptosaurus as well. The overall body type is similar to that of Tyrannosaurus but more streamlined, longer legs and longer arms with three fingers on each hand instead of two with digit one's (or finger one, the equivalent of the thumb) claw being the biggest.

When sketching the body, press lightly with the pencil. I, myself, ended up redoing this several times until I was satisfied with what I drew so erasing a failed attempt is a lot easier when drawn lightly. Also, when using watercolors, the paint is going to be the bold, hard edges you need, not the pencil lines. If all goes well, no pencil lines will be visible in the finished product.

Once the drawing is done its time to apply the first layer of paint. With watercolors, you apply the paint from the tube onto a plastic pallet and let them dry. Then, you take wet brushes and gather color from the dried clumps of paint to apply to the paper. These dried clumps of paint can last for years before depleted (depending on how much is on the pallet).

The first thing I want to do is apply a base color. I am going to make this Dryptosaurus green. I'm going to take a little bit of green paint and mix it with a LOT of water. Then I take a wet brush and apply a light layer of watered-down paint over my entire dinosaur.

I've said it many times before; nothing in nature is ever one solid color. What I do while my layer of green is still sopping wet, is add some other bits of color. Not much, just enough to make the dinosaur look not so uniform. Video time!

Hope that made sense. Then we wait for this first layer to dry. Normally, depending on how much paint you have on the paper, it takes about ten minutes for a layer to dry. I like to paint with the TV on to keep me entertained. My grandmother, who also paints watercolors, used to use a hairdryer to speed up the process. Its up to you. After the first layer is all dry its time to add some shading. Shading is crucial to making anything look realistic. Another video woooo!

When my first wave of shading is complete the dinosaur looks like this.

Now we can start adding more detail. I take a fine brush and use the same darker shade of green that I used for the shadow to make wrinkles and scales on the body. I also am going to add feathers to this guy since we know from fossil evidence that at least some other tyrannosauroids had them.

This stuff takes practice, as does anything in life. Just keep at it and have fun. Don't be afraid to go back and re-apply shading to something that didn't come out dark enough. Generally, a layer of watercolor paint will dry much lighter than when it was applied. My finished product looks like this.

Don't get frustrated if it doesn't come out exactly the way you wanted it. I've been painting for over twenty years and to this day I don't think I have ever produced something I was 100% satisfied with. Nobody is perfect at anything! The good thing to get out of this is having the knowledge that you can only get better with practice!

Join me next week as I interview another extremely talented paleo-artist!

Works Cited

Cope, E.D. (1866). "Discovery of a gigantic dinosaur in the Cretaceous of New Jersey." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 18: 275-279.

Holtz, T.R. (2004). "Tyrannosauroidea." Pp. 111-136 in Weishampel, Dodson and Osmolska (eds). The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press, Berkeley.

Xu, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Q.; Xing, L.; Sullivan, C.; Hu, D.; Cheng, S. et al. (2012). "A gigantic feathered dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China" (PDF). Nature 484: 92–95. doi:10.1038/nature1090

Like all of my drawings, I must first start out with a rough sketch to make sure I am getting the proportions right. Unfortunately, Dryptosaurus is known from only several bones and not a full skeleton. When this happens my best bet is to reference close relatives to Dryptosaurus. Dryptosaurus was a tyrannosauroid but not a tyrannosaurid (confusing I know) so it was a bit more primitive than its big-headed, two-fingered cousins like Tyrannosaurus. When dealing with Dryptosaurus I look at animals like Eotyrannus and Appalachiosaurus as guides. Both of these dinosaurs are not only related to Dryptosaurus, but according to the bones on the fossil record, they visually resembled Dryptosaurus as well. The overall body type is similar to that of Tyrannosaurus but more streamlined, longer legs and longer arms with three fingers on each hand instead of two with digit one's (or finger one, the equivalent of the thumb) claw being the biggest.

When sketching the body, press lightly with the pencil. I, myself, ended up redoing this several times until I was satisfied with what I drew so erasing a failed attempt is a lot easier when drawn lightly. Also, when using watercolors, the paint is going to be the bold, hard edges you need, not the pencil lines. If all goes well, no pencil lines will be visible in the finished product.

Once the drawing is done its time to apply the first layer of paint. With watercolors, you apply the paint from the tube onto a plastic pallet and let them dry. Then, you take wet brushes and gather color from the dried clumps of paint to apply to the paper. These dried clumps of paint can last for years before depleted (depending on how much is on the pallet).

The first thing I want to do is apply a base color. I am going to make this Dryptosaurus green. I'm going to take a little bit of green paint and mix it with a LOT of water. Then I take a wet brush and apply a light layer of watered-down paint over my entire dinosaur.

I've said it many times before; nothing in nature is ever one solid color. What I do while my layer of green is still sopping wet, is add some other bits of color. Not much, just enough to make the dinosaur look not so uniform. Video time!

When my first wave of shading is complete the dinosaur looks like this.

This stuff takes practice, as does anything in life. Just keep at it and have fun. Don't be afraid to go back and re-apply shading to something that didn't come out dark enough. Generally, a layer of watercolor paint will dry much lighter than when it was applied. My finished product looks like this.

Don't get frustrated if it doesn't come out exactly the way you wanted it. I've been painting for over twenty years and to this day I don't think I have ever produced something I was 100% satisfied with. Nobody is perfect at anything! The good thing to get out of this is having the knowledge that you can only get better with practice!

Join me next week as I interview another extremely talented paleo-artist!

Works Cited

Cope, E.D. (1866). "Discovery of a gigantic dinosaur in the Cretaceous of New Jersey." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 18: 275-279.

Holtz, T.R. (2004). "Tyrannosauroidea." Pp. 111-136 in Weishampel, Dodson and Osmolska (eds). The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press, Berkeley.

Xu, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Q.; Xing, L.; Sullivan, C.; Hu, D.; Cheng, S. et al. (2012). "A gigantic feathered dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China" (PDF). Nature 484: 92–95. doi:10.1038/nature1090

Thursday, August 30, 2012

Living Fossil: The Dinosaur's Archosaur Relative

A few weeks ago I wrote about a living fossil, the horseshoe crab. Today I will be going over another type of modern prehistoric creature that is near and dear to my heart, crocodilians. Crocodilians (including crocodiles, alligators, caimans and gharials) have been wildly successful since the Triassic. They started to become successful right alongside the first dinosaurs. Unlike the dinosaurs, however, (many)crocodilians have remained virtually unchanged since the Mesozoic. Dinosaurs, on the other hand, evolutionarily experimented with countless different body types, sizes and niches only to end up with just one variety adaptable enough to survive into today (birds).

During the Mesozoic era there were crocodilians that were more or less the same as the ones living today. Some, however, did evolve a bit differently. There are a number of strange and different kinds of crocodilians on the fossil record. Some were more land-adapted, some had wildly different skulls for functions scientist can only guess at today and some, like Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus, grew to epic sizes and more than likely were preying upon dinosaurs much like smaller modern crocodiles prey on land mammals today.

Today, crocodiles and their kin remain one of the most adaptable and successful reptiles, but why? Here is an animal that has remained virtually unchanged for 250 million years. They must be doing something right.

Lets start by looking at a crocodilian's lifestyle. They don't require much. They spend time in and out of the water (which doesn't need to be that clean) and tend to be generalist predators all around. A crocodilian won't hesitate to eat any kind of animal, including rotting carcasses other meat eaters would pass on. Furthermore, like many reptiles, crocodilians are cold blooded or ectothermic. Because of this their metabolisms are much slower than an endothermic animals's and therefore don't require as much food in order to stay alive. In fact, after a large meal, a large crocodile can go to a year's time without eating if it has to.

When compared to other modern reptiles like testudians and squamates, crocodilians have a few advantages. The tough scales on their backs, called scutes, function like solar panels, allowing the animal to absorb energy from the sun and warm the body up much more quickly than most other modern reptiles. Crocodilians have a four chambered heart and the functional equivalent of a diaphragm. They also have a one-way breathing system much like their closest living relatives, the birds. This means that instead of mixing inhaled and exhaled air in the lungs when breathing (like we do) fresh air is continuously being taken through the body (more efficient). Fun fact: alligators have the most powerful jaws of any living animal ever recorded (over 2,000 pounds per square inch).

American Alligators (Crocodilus mississipiensus) have recently become the interest of medical doctors because of their immunity to a vast variety of pathogens. In a lab setting, alligator serum and human serum were both exposed to twenty three types of harmful bacteria including MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus), E. colli and Salmonella. The Alligator serum fought off all of them with flying colors. The human serum only managed to fight off eight. Furthermore, the protiens in alligator blood were also discovered to be totally resistant to Candida albicans (fungus), HIV and Herpes (viruses). This could be due to the fact that alligators commonly live in environments where the water isn't exactly the cleanest. Lets just say if a human were to go wading around in there with any open wounds there is a solid chance that individual would get an infection of some kind. Alligators, however, get bloody injuries all the time due to fighting amongst themselves for dominance. Its a fundamental part of their social behavior. Its not uncommon to see alligators missing body parts from fights with rivals. Yet despite these seemingly mortal wounds, the alligators almost always heal up no problem even with the bacteria and other nasty pathogen-infested water they are constantly swimming around it. Jaws, armor and metabolism aside, the crocodilian's immune system very well may be its secret to success. Sadly, even the mighty crocodilians were found to be sensitive to pollution caused by humans.

Who knows? If scientists manage to sequence the proteins in alligator blood, we may have some powerful new medicine in the future to fight off seemingly incurable diseases!

Works Cited

Bird, July. Antibiotics from alligators. Nature Publishing Group 8.5 (2008): 326-26.

Fleshler, David. Alligators' 'ferocious' immune system could lead to new medicines for people. Sun-Sentinel. 14 Aug. 2006.

Avasthi, Amitabh. "Alligator Blood May Lead to Powerful New Antibiotics." National Geographic.

Farmer, C. G., and Sanders, K. (January 2010). "Unidirectional Airflow in the Lungs of Alligators". Science 327 (5963): 338–340. doi:10.1126/science.1180219. PMID 20075253. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/327/5963/338.

|

| In the workplace I get the pleasure of dealing with the Dwarf Caiman (Paleosuchus palpablrosus), the smallest and most heavily armored member of Crocodilia. |

During the Mesozoic era there were crocodilians that were more or less the same as the ones living today. Some, however, did evolve a bit differently. There are a number of strange and different kinds of crocodilians on the fossil record. Some were more land-adapted, some had wildly different skulls for functions scientist can only guess at today and some, like Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus, grew to epic sizes and more than likely were preying upon dinosaurs much like smaller modern crocodiles prey on land mammals today.

|

| During the late Cretaceous, crocodilian, Kaprosuchus, threatens the dinosaur, Nigersaurus. |

Today, crocodiles and their kin remain one of the most adaptable and successful reptiles, but why? Here is an animal that has remained virtually unchanged for 250 million years. They must be doing something right.

Lets start by looking at a crocodilian's lifestyle. They don't require much. They spend time in and out of the water (which doesn't need to be that clean) and tend to be generalist predators all around. A crocodilian won't hesitate to eat any kind of animal, including rotting carcasses other meat eaters would pass on. Furthermore, like many reptiles, crocodilians are cold blooded or ectothermic. Because of this their metabolisms are much slower than an endothermic animals's and therefore don't require as much food in order to stay alive. In fact, after a large meal, a large crocodile can go to a year's time without eating if it has to.

|

| Come on in! The water's...um...actually don't. |

When compared to other modern reptiles like testudians and squamates, crocodilians have a few advantages. The tough scales on their backs, called scutes, function like solar panels, allowing the animal to absorb energy from the sun and warm the body up much more quickly than most other modern reptiles. Crocodilians have a four chambered heart and the functional equivalent of a diaphragm. They also have a one-way breathing system much like their closest living relatives, the birds. This means that instead of mixing inhaled and exhaled air in the lungs when breathing (like we do) fresh air is continuously being taken through the body (more efficient). Fun fact: alligators have the most powerful jaws of any living animal ever recorded (over 2,000 pounds per square inch).

|

| Alligator mouth. Yes, I took this picture. No, there was no zoom. |

American Alligators (Crocodilus mississipiensus) have recently become the interest of medical doctors because of their immunity to a vast variety of pathogens. In a lab setting, alligator serum and human serum were both exposed to twenty three types of harmful bacteria including MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus), E. colli and Salmonella. The Alligator serum fought off all of them with flying colors. The human serum only managed to fight off eight. Furthermore, the protiens in alligator blood were also discovered to be totally resistant to Candida albicans (fungus), HIV and Herpes (viruses). This could be due to the fact that alligators commonly live in environments where the water isn't exactly the cleanest. Lets just say if a human were to go wading around in there with any open wounds there is a solid chance that individual would get an infection of some kind. Alligators, however, get bloody injuries all the time due to fighting amongst themselves for dominance. Its a fundamental part of their social behavior. Its not uncommon to see alligators missing body parts from fights with rivals. Yet despite these seemingly mortal wounds, the alligators almost always heal up no problem even with the bacteria and other nasty pathogen-infested water they are constantly swimming around it. Jaws, armor and metabolism aside, the crocodilian's immune system very well may be its secret to success. Sadly, even the mighty crocodilians were found to be sensitive to pollution caused by humans.

|

| Alligator that had lost it's tail in a fight. The wound healed over no problem. |

Who knows? If scientists manage to sequence the proteins in alligator blood, we may have some powerful new medicine in the future to fight off seemingly incurable diseases!

Works Cited

Bird, July. Antibiotics from alligators. Nature Publishing Group 8.5 (2008): 326-26.

Merchant, Mark. Differential protein expression in alligator leukocytes in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide injection. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology: Genomics and Proteomics 4.4 (2009): 300-04.

Fleshler, David. Alligators' 'ferocious' immune system could lead to new medicines for people. Sun-Sentinel. 14 Aug. 2006.

Avasthi, Amitabh. "Alligator Blood May Lead to Powerful New Antibiotics." National Geographic.

Farmer, C. G., and Sanders, K. (January 2010). "Unidirectional Airflow in the Lungs of Alligators". Science 327 (5963): 338–340. doi:10.1126/science.1180219. PMID 20075253. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/327/5963/338.

Thursday, August 16, 2012

Animals Then and Now: Choose Your Weapon

This week I'm going to go back into my comfort zone of comparing extinct dinosaurs to modern animals in order to better understand them. Specifically, I would like to talk about animal weaponry. Many animals, alive and extinct, have weapons to either help defend themselves from being eaten or to help them catch/kill other animals for themselves to eat. At work I get to see some of these dangerous animals up close (sometimes too close!).

If you notice, predatory animals tend to all have similar weapons to help them catch their prey regardless of whether or not they are related to each other. This is because the ultimate goal of every predator is the same: catch the prey. Check out this claw from an African Lion.

See its shape? Its hooked. Hooks are great for catching things. They are sharp at the tip to pierce the skin of whatever they are hunting and they are curved to prevent whatever they are catching from pulling away. Even us humans use hooks to catch fish. Its a simple yet highly effective design. It isn't designated to claws either. Predatory animals that can't use claws many times use teeth instead like snakes.

Now check out THIS weapon.

Same structure as the lion just a lot bigger right? Its from an animal not remotely related to lions though. That's a hand claw from an Allosaurus. Even though Allosaurus and African Lions don't share much in common when it comes to their DNA. They have many of the same adaptations thanks to convergent evolution (which I talked about in my very first post!). So what does this tell us about dinosaurs like Allosaurus? Well, a lion will use its hooked claws to hold on to struggling prey that is many times larger than the lion itself. It can be safe to assume that Allosaurus was doing something similar with its claws. Since Allosaurus was much larger than a lion and its claws were also much larger than a lion's, it makes sense that it could have been hunting animals that were also much larger like the myriad of other dinosaurs it shared its habitat with during the Jurassic.

Extinct predators that didn't really have dangerous claws (or any claws) would have used other things. Check out Tyrannosaurus rex. Tiny arms, HUGE head with teeth...that are curved! Not really related to snakes that closely but similar adaptations none the less.

Not all predatory weapons HAVE to be hooks either. As long as they catch prey they are successful. Crocodillians don't really have curved teeth but they do have powerful jaws that do a good job of locking down on prey hard enough so that it can't escape. Many turtles and fish create a vacuum under the water to suck prey into their mouths. Amphibians don't have much in the way of teeth and absolutely nothing when it comes to claws yet they are highly effective predators in their own right thanks to their sticky tongues and fast mouths.

What about the prey? They certainly aren't interested in catching any other animals. The weapons they DO have are usually designed to keep predators as far away as possible. Think about an animal like a porcupine. They have many sharp quills coming out from their backs. Most predators have to deal with the dilemma of working around those things which requires them to keep a distance between the two of them. Not an easy prey animal. Other animals have things like armor on their hides like armadillos and tortoises to discourage predators from attacking. How about dinosaur weapons? Here is a tail spike from a Stegosaurus.

Its sharp. But it isn't curved or hooked. Without ever seeing the animal alive I can guess that it's first line of defense against something like Allosaurus would be to keep the predator away and discourage it from attacking in the first place. If it HAD to stab with the spikes, they could easily be removed after the damage is done because they are straight. The last thing a prey animal wants to do is hold on to its attacker!

Works Cited

Holtz, Thomas R., and Luis V. Rey. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House, 2007. Print.

McGhee, G.R. (2011). Convergent Evolution: Limited Forms Most Beautiful. Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge (MA). 322 pp.

Sabuda, Robert, and Matthew Reinhart. Dinosauria. Kbh.: Carlsen, 2007. Print.

|

| Dangerously Cute!!! (Baby Arctic Foxes) |

If you notice, predatory animals tend to all have similar weapons to help them catch their prey regardless of whether or not they are related to each other. This is because the ultimate goal of every predator is the same: catch the prey. Check out this claw from an African Lion.

|

| African Lion front claw (cast) |

See its shape? Its hooked. Hooks are great for catching things. They are sharp at the tip to pierce the skin of whatever they are hunting and they are curved to prevent whatever they are catching from pulling away. Even us humans use hooks to catch fish. Its a simple yet highly effective design. It isn't designated to claws either. Predatory animals that can't use claws many times use teeth instead like snakes.

Now check out THIS weapon.

|

| Allosaurus hand claw (cast) |

Same structure as the lion just a lot bigger right? Its from an animal not remotely related to lions though. That's a hand claw from an Allosaurus. Even though Allosaurus and African Lions don't share much in common when it comes to their DNA. They have many of the same adaptations thanks to convergent evolution (which I talked about in my very first post!). So what does this tell us about dinosaurs like Allosaurus? Well, a lion will use its hooked claws to hold on to struggling prey that is many times larger than the lion itself. It can be safe to assume that Allosaurus was doing something similar with its claws. Since Allosaurus was much larger than a lion and its claws were also much larger than a lion's, it makes sense that it could have been hunting animals that were also much larger like the myriad of other dinosaurs it shared its habitat with during the Jurassic.

|

| Allosaurus |

Extinct predators that didn't really have dangerous claws (or any claws) would have used other things. Check out Tyrannosaurus rex. Tiny arms, HUGE head with teeth...that are curved! Not really related to snakes that closely but similar adaptations none the less.

|

| Tyrannosaurus rex |

Not all predatory weapons HAVE to be hooks either. As long as they catch prey they are successful. Crocodillians don't really have curved teeth but they do have powerful jaws that do a good job of locking down on prey hard enough so that it can't escape. Many turtles and fish create a vacuum under the water to suck prey into their mouths. Amphibians don't have much in the way of teeth and absolutely nothing when it comes to claws yet they are highly effective predators in their own right thanks to their sticky tongues and fast mouths.

|

| With a tongue like this Palm Salamander's who needs teeth? |

What about the prey? They certainly aren't interested in catching any other animals. The weapons they DO have are usually designed to keep predators as far away as possible. Think about an animal like a porcupine. They have many sharp quills coming out from their backs. Most predators have to deal with the dilemma of working around those things which requires them to keep a distance between the two of them. Not an easy prey animal. Other animals have things like armor on their hides like armadillos and tortoises to discourage predators from attacking. How about dinosaur weapons? Here is a tail spike from a Stegosaurus.

|

| Stegosaurus tail spike (cast) |

Its sharp. But it isn't curved or hooked. Without ever seeing the animal alive I can guess that it's first line of defense against something like Allosaurus would be to keep the predator away and discourage it from attacking in the first place. If it HAD to stab with the spikes, they could easily be removed after the damage is done because they are straight. The last thing a prey animal wants to do is hold on to its attacker!

|

| Stegosaurus |

Works Cited

Holtz, Thomas R., and Luis V. Rey. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House, 2007. Print.

McGhee, G.R. (2011). Convergent Evolution: Limited Forms Most Beautiful. Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge (MA). 322 pp.

Sabuda, Robert, and Matthew Reinhart. Dinosauria. Kbh.: Carlsen, 2007. Print.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)