We should know by know that birds are living dinosaurs and are every bit as fascinating. Coming from a background working with living animals, myself I am really excited to share an interview I had with Katrina van Grouw, author of The Unfeathered Bird.

Katrina van Grouw is a former curator of the ornithological collections at London’s Natural History Museum, a taxidermist, experienced bird bander, successful fine artist and a graduate of the Royal College of Art. She is the author of Birds, a historical retrospective of bird art, published under her maiden name Katrina Cook. The creation of The Unfeathered Bird has been her lifetime’s ambition. I bought this book and let me say it is amazing! Anyone remotely interested in birds will enjoy and learn a whole lot from it.

Question 1: At what age did you become interested in birds? Were they always a subject of your art?

KV: As far back as I can remember; I was passionate about birds and natural history. I had a whole string of pet birds and other animals. The companion of my early childhood was a much loved pet chicken called Hilda (which grew up to be a cockerel). Later on I reared a jackdaw which used to fly along next to me when I rode my bicycle. And I built up a little ‘museum’ at home, of birds’ wings, skulls, old nests and feathers etc., and used to persuade my mum to take me to the natural history museum at Tring nearby, at least once a week in every school holiday, throughout my entire childhood. (This museum now houses the London Natural History Museum’s ornithology collections, and it was here that I later worked as a curator).

As a 4 year old I was always drawing eagles and vultures. And dogs – I’ve always felt much closer to dogs than to people. Then, as my interest in birdwatching developed, round about the age of 11, I attempted to draw all the birds on the British list. I managed to get about half way before the school art teacher moulded me into believing that ‘real artists don’t draw birds’. Although this was rather cruel, it was followed by a traditional and rigid early art training, with challenging still life compositions and regular life drawing sessions from a human model which has been to my advantage as a draughtsman.

|

Question 2: What medium do you most prefer to use for your art? Any particular reason why?

KV: All the drawings for The Unfeathered Bird are in pencil (I use a B or a 2B, kept very sharp), then were changed digitally into sepia afterwards. Before this, I used to draw large dramatic sea cliffs in graphite, with very small birds and the foam on the water added in white paint. And before this, I was a printmaker, working primarily in drypoint – a type of engraving - on enormous copper plates.

What all these things have in common is their directness, and I guess that says a lot about me. I’ve done lots of paintings over the years, and lots of printmaking in other media, for example etching (where you have to protect the pale areas while you etch the dark bits) and relief printing (where you have to remove the white areas and leave the dark). But none of these media do it for me at all. Much too long-winded and indirect! And colour? - An irritating and unnecessary distraction!

|

| Albatross by Katrina Van Grouw |

Question 3: Is there any particular artist who particularly inspired you growing up? How about today?

KV: Growing up, my tastes were fairly predictable for a young person learning about art history. I went through a Salvador Dali phase (everyone does). Then I was blown away by the Pre-Raphaelites (everyone is). After that period of obligatory technique-worship, I discovered Samuel Palmer who fuelled my passion for the English countryside. I still love Palmer’s work, but prefer the poignancy of the early 20th Century English graphic artists working before and between the Wars: Eric Ravilious and the Nash brothers amongst others.

I’m also a great fan of the symbolist painters and printmakers, Arnold Bocklin, Gustav Moreau, and Odilon Redon, all of whom have something to answer for in my work.

On the natural history front, George Stubbs was, and is, a great shining hero in the sky.

But no-one has had a more profound influence on me than John James Audubon. Not only did The Birds of America inspire my early drypoints of birds during and shortly after college years but, more importantly, the knowledge of Audubon’s long struggle to produce it kept me going throughout the production of The Unfeathered Bird. It was difficult not to see parallels between the two projects. Like mine, Audubon’s idea did not fit squarely into a niche; it was both art and science. He had to fight for it, and believe in it. He worked life-sized, like me. He was uncompromising and pig-headed like me, and put his book before everything and everyone else - like me. Both books took over 20 years to come to fruition. And Audubon had to get his published in England while I had to get mine published in America. Now, I’m definitely not saying I’m on a par with Audubon – but only that – when the odds stacked up against me and I wanted to give it all up and just fall apart – I’d think about what Audubon would do, and carry on.

|

| Front cover of Katrina's new book featuring a peacock. |

Question 4: When did you decide to pursue a career in illustration?

KV: I didn’t! In fact I’ve never really thought of myself as an illustrator at all, and have only illustrated a couple of books other than The Unfeathered Bird.

My first degree was in Fine Art, and that’s how I always saw myself. In my student days ‘illustration’ was a bit of a dirty word – especially as it was widely assumed that if natural history was your subject matter then you were an illustrator; end of story. I had countless arguments with college tutors who thought it their mission to tell me that I’d joined the wrong course! My college friends and I were always seeking a watertight definition of the difference between fine art and illustration. My definition now is that fine art is produced with the intention of selling or exhibiting it in its original state, whereas illustrations are produced primarily for reproduction. Many a work of fine art, reproduced, can serve as an illustration in a suitable context; and many a fine artist would do well to take a look at the skill and draughtsmanship inherent in illustration. When it comes to drawing ability, most illustrators can wipe the floor with today’s fine artists!

But if you’d like to know when I decided to pursue a career in art – well, it was a reluctant choice and I only submitted to it when I realized that I had no hope of anything else, several years after leaving school and unable to get a place on a science course. I’d shown my drawing ability very young, you see, and had been treated like a child prodigy, so I wasn’t qualified to do anything but art. To be honest though, art was actually what I really wanted to do all along (and I’m certainly no scientist) - but I would have preferred to have been allowed to make my own decisions in my own time!

|

| Night Heron by Katrina van Grouw |

Question 5: You have a degree in Natural History Illustration. How much of each field (science and art) does this cover?

KV: In fact my first degree (my BA) was in Fine Art, and after this I went on to do a Master’s degree (MA) in Natural History Illustration. Unfortunately, that particular course, at the Royal College of Art, was a bitter disappointment. I’d expected lectures in historical natural history illustration and a vibrant art/science scholarly atmosphere, but there was nothing like this at all. The tutor encouraged field drawing, and arranged for reduced price entry to London Zoo, which is all very good. However, I had been taken on to do a specific project – an illustrated thesis on bird anatomy (really a research degree), which I was left to pursue unsupervised for the entire duration (2 years). The course has now ceased to run.

|

| Synanthedon by Katrina van Grouw. |

Question 6: Have you done other illustrations of subjects besides birds?

KV: Yes, indeed, but they’re not all what you might call illustrations.

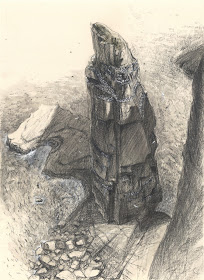

When I first became a printmaker and learned to do drypoints, I’d walk for miles along the chalk downs carrying lots of tiny metal plates that I’d engrave onto directly. My subject was the landscape and its archaeological features – chalk figures, burial mounds, standing stones etc. (more about my love affair with the chalk downs in question 12…). I built up quite a collection which I someday intend to publish as a set.

The move back to natural history subjects was a sudden one, when I remembered where my real interest lay, and I was very much inspired by historical natural history illustrations and museum collections. Birds were my primary interest, but I also did a lot of work from botanical subjects and even molluscs.

So, the landscapes turned to birds and, over the years, the birds became smaller and smaller until they were just tiny shapeless specks in the landscape again (though this apparently seamless transition was, in reality, punctuated with soul-wrenching intellectual crises). The large landscape – or rather seascape - drawings were produced in situ; perched on cliff tops overlooking caves or stacks or natural arches.

People have told me that they can see a similarity between the coastal geology drawings and the anatomical work. This pleases me immensely, as in both cases I was endeavouring to convey the underlying structure and solidity: what’s going on underneath.

In terms of proper illustration, I’ve actually done very little (The Unfeathered Bird which I conceived, wrote, and designed myself; and two bird books for other authors) but I did illustrate a book called A Field Guide to the Smaller Moths of South-East Asia for the Natural History Museum way back in 1992. Photographs were used for the colour plates, but I produced 50 or so drawings of the head structure of various species; pin-head size or smaller (the moth heads - not the drawings) and a few resting postures of whole moths.

|

| head of Nemophora dicisella (a moth) by Katrina can Grouw. |

Question 7: Even though you have no formal scientific training, you eventually became the curator of ornithology at the Museum of Natural History in London. How did you achieve such an amazing position? What was it like working there?

KV: That sounds very grand, but I was actually one of a team of five curators, each with a different responsibility for a part of the collections. (In the UK, curators are more like collections managers in the US, i.e. caretakers as opposed to researchers). I was jointly responsible for skins, and had overall responsibility for specimen preparation and repair. We also all received and supervised scientific visitors to our own area, and answered public enquiries, issued loans etc. It was the knowledge I’d gained in my early anatomical investigations many years before, as well as my understanding of moult and ageing as a bird bander that landed me the job, and especially the fact that I knew how to prepare bird study skins.

Much of the job was just like working in any other big institution - meetings about meetings; corporate policies; health & safety legislation etc. etc. But I loved the place, and was proud to be a part of it; it made me feel like a swan, as opposed to the worthless ugly duckling I’d felt before, and there’s not a day that passes when I don’t wish I was still there.

| Beacon Hill by Katrina van Grouw. |

Question 8: You are a qualified bird bander and have travelled all over the globe working with wild birds. Do you have a favorite experience doing this? Was there any particular species of bird you were banding most or trying to band?

KV: Bird banding is all about identifying individual birds so that you can study population changes and bird movements with greater accuracy. All data is potentially useful, but specific projects, with a particular aim, are of the greatest scientific value. I’m really not a scientist at all, but I enjoy the detective work involved in getting as much information as possible from a bird in the hand – a single feather can give a vital clue about a bird’s age, for example. So I could contribute to the scientific work of others in my own way.

I initially trained to be a bander because I wanted to take part in expeditions to remote places – not the best reason, I know! My first expedition was 3 months spent in Senegal, West Africa, banding European migrants in their winter quarters and studying the movements of migrants through the Sahel. So although we were surrounded by all sorts of resident African birds that most of us had only seen in books, our target species were actually the common migrants we were used to seeing in England. It was a fantastic trip and I saw some superb wildlife: patas monkeys galloping across the desert; great flocks of queleas swirling in the air like swarms of insects; lakes covered in bird life – flamingos, pelicans, whistling ducks and wading birds of every description; crowned cranes dancing in the desert; a puff adder swimming through a moonlit swamp amongst the roosting birds... It was all the more poignant for me because until then I’d never even been on an aeroplane!

Question 9: Have you ever received any negative feedback on any of your work? How do you respond to that?

KV: Yes; but only from idiots. And I respond very badly!

But seriously – what hurts most is unjust criticism, without good reason – people making negative comments just to make themselves look clever; and criticism which has no foundation. For example, dozens of reviewers have said The Unfeathered Bird is beautifully written, but one person said the writing is weak. For me, the negative impact of that outweighs all the accumulated effect of the positive comments. I worked so hard, for so long, and sacrificed so much for this book, that it hurts to get niggling little criticisms like that.

However, 99.9% of my reviews have been simply glorious – some, deeply moving - and have far, far, exceeded expectations.

|

| Pomarine Skuas by Katrina van Grouw. |

Question 10: Art and illustration is such a diverse field. It has also changed dramatically within the past decade or so. What advice would you have to give an aspiring artist today?

Ooh, nice question – can I give two?

KV:

Piece of advice No. 1:

Draw. Everything. All the time. Keep a sketchbook. But don’t fret and worry about the drawings looking good to others. Let drawing become an exploration; stay focused and full of integrity about the quality of your observation; be your own hardest critic. A sketchbook is for you and you alone.

Piece of advice No. 2:

Don’t be too opposed to the option of taking a day job. I know; there’s a lot of stigma against it – people think you’ve given up, or sold out, or couldn’t make it as an artist. This is bullshit! As long as you continue to make time for artwork, a part time or even a full time job gives you self-esteem, contact with people, daily routine and money. Money’s really important actually. Life is too short to have to steal leftover food or burn the furniture to keep warm (yes, I’ve done both these things). But always remember: when anyone asks you what you do, say that you’re an artist.

And this one’s for anyone; not just artists:

Be careful what you give up. It might be a long time before you manage to get it back.

|

| Wedge Tail Eagle by Katrina van Grouw. |

Question 11: What is your favorite bird? Did you have a favorite bird when you were a child?

KV: Well I like jackdaws, for obvious reasons, and that may well have been my favourite species as a child. But it’s seabirds, now, that really turn me on. I love everything about them – even (well, probably especially) the smell. And the sound. There’s nothing so wonderful as being perched on a clifftop above a seabird colony when the breeding season is in full swing.

Fulmars are great – I just love it when they vomit on you.

Storm Petrels are simply magical.

Cormorants are cool (our mutual friend Niroot and I decided that I’d be a cormorant if I were a bird).

But my favourite seabirds of all are Frigatebirds. They’re enormous, black, piratical, primitive-looking things, and you can just imagine Pterosaurs when you see them soaring overhead. They’re so exciting to watch, too. They don’t swim; they can barely perch, but they fly like demons! Best seen against a tropical stormy sky, in pursuit of a shining, white, comet-tailed, tropicbird...

|

| Skeletals of a Frigatebird pursuing a Tropicbird by Katrina van Grouw. |

Question 12: Do you have any other hobbies or interests (not necessarily ornithology related)?

KV: Hmm, let me see… I like red wine.

I love going to the cinema. My friends are appalled by the intellectual level of the films I like to see. But I don’t want cultural stimulation – I go there to escape, on my own. Meteorological disaster movies, far-fetched archaeological adventure films, science fiction and anything to do with superheroes do very nicely.

But my greatest passion is for long walks in chalk down landscape – especially the stretch of 100 miles or so that runs between Buckinghamshire (where I live), down through Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Wiltshire and is covered at the far end with ancient earthworks: ditches, burial mounts, barrows, hill figures of horses cut into the chalk; standing stones; and odd isolated clumps of trees. I love the feeling of knowing the landscape intimately, as far as the eye can see. I’ll happily disappear up there for days on end with my dog, Feather. Unfortunately I get slightly afraid of sleeping outdoors on my own at night – or more accurately – I’m scared of getting scared. Probably a good thing, on reflection, as it’s the only thing that keeps me from going completely feral.

|

| Pouter Pigeon with an inflated condom in its crop. |

Question 13: Your book, The Unfeathered Bird, features many amazing illustrations of bird anatomy all illustrated by you. Was any particular one especially memorable to do? Did any give you unexpected trouble?

KV: Unexpected trouble? – oh yes! Drawing the skinned birds was unbelievably difficult. They go all floppy and shapeless. I could just have the skinned carcass lying on the table, and re-construct the position mentally, with reference to images of living birds, or I could rig them up with all sorts of wires and threads and things – whatever would keep them in the position I wanted. The pouter pigeon with its crop inflated was unforgettable. We actually ended up pushing a condom down the bird’s throat then blowing it up like a balloon!

The greatest challenge though was drawing skeletons in lifelike postures from bones that were not articulated; the ones in scientific reference collections in natural history museums. The scientists using these collections need to study the articulating surfaces of individual bones, so it’s important that they’re not glued or wired together. I worked out quite a clever solution: I would draw the skeleton of another bird already prepared in the position I wanted, then rub out and re-draw each bone in turn, with reference to the respective bone of the desired species. It works remarkably well, but you have to really know your birds. The Magnificent Frigatebird (my favourite image from the book) was drawn in this way, from a disarticulated skeleton on loan from the Field Museum, Chicago, and modelled from the position of the Tropicbird it’s chasing. As a huge fan of both frigatebirds and tropicbirds (with feathers on), it was important for me to get it right, and do justice to the dynamism and excitement of a real-live aerial pursuit.

Thank you so much Katrina! Be sure to check out Katrina van Grouw's website and buy her book! It has quickly become one of my favorites in terms of imagery alone. Stay tuned for Sunday's Prehistoric Animal of the Week! Farewell until then!

No comments:

Post a Comment